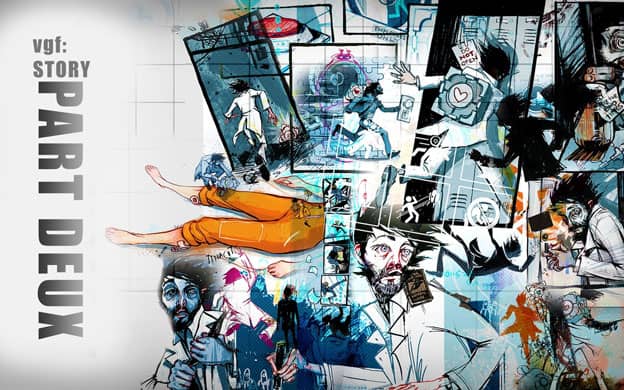

VGF: The Art Of Storytelling Part 2

Storytelling fascinates me. It’s so fluid, and it can fit itself into several different methods or design philosophies. This is why we have various types of media in which we find stories. For example, novels, comic books, and movies all tell stories, but none of them do it in the same way. Novels contain large blocks of text, comic books show us images and text juxtaposed (for more on what makes this type of media so unique, check out Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics ), and movies deliver animated images along with audio.

So which of these forms of media are video games the closest to? Well, this has changed several times over the past three decades.

In the old days, several video games took their cues from novels, telling their stories completely in text. The original Zork game is a great example. (If you have no idea what that is, either Google the phrase “you may be eaten by a Grue,” or break free from your bounds at the title screen of Black Ops and enter “ZORK” into the computer terminal.)

In the NES and Super NES eras, video games moved into a more comic book-style form of storytelling, with simple animations and “word bubble” type blocks of text. Look at old SNES JRPGs like Final Fantasy VI and Chrono Trigger for examples.

In the PSOne era, video games finally moved into the realm of movie-type storytelling. (The SEGA CD experimented with this earlier, but its attempts at making choose-your-own-adventure-style interactive movies pretty much fell flat.) The PSOne generation brought to life true FMVs (full motion videos), and video game stories finally started coming into their own. While games like Final Fantasy VII retained some of the comic book-style word bubble dialogue, it was games like this that pushed the industry into the realm of using movie-like chunks of non-interactive video. It eventually became commonplace for cutscenes to be the go-to method of telling a video game story. (It should be noted, though, that comic book-style dialogue is still often found mixed in with the cutscene approach. Just look at The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword for a very recent example.)

So we’ve seen video games transition from novel-type storytelling to a more comic bookish approach, and finally become more like films. For almost three generations, we’ve been stuck in this “video games are like movies” mentality. But a video game is simply not a novel, comic book, or film. Sure, games have a few things in common with these other types of media, but a video game is interactive. Video games should tell stories in their own way, in a way that no book or movie could duplicate.

And that’s why I think it’s so exciting to find the safe house scribbling in Left 4 Dead, or the mad scrawling of the Rat Man in Portal. (“The cake is a lie.”) I spent a good deal of words last week explaining how each of these two games tells its tale in a way that would satisfy your English teacher’s strict guidelines, so I won’t dig too deeply into that this week. (You can read all that goodness here though.) The point was that inserting little side stories that players are free to discover for themselves—or ignore altogether if they choose to do so—is something that video games excel at. This isn’t a tactic completely unique to video games, as several comic books and films do these types of things, but video games can do this so much more effectively than films or comic books.

This is just one area where we can see video game storytelling breaking through the boundaries set by other types of media. Now, for another example of how storytelling is evolving, I’d like to compare a classic from last generation, Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty, with a game that’s undoubtedly destined to be considered a classic from this generation, Uncharted 2: Among Thieves.

In MGS2, there’s a scene—it’s right after the Harrier fight, if you’re interested in seeking it out—in which the scaffold Raiden is standing on begins to fall apart, and he is left dangling precariously over the ocean below while holding onto a piece of bent metal. This is done in a cutscene. Eventually, the player will get to climb hand-over-hand on this piece of metal and drop onto a pipe below, and this particular event is done in gameplay.

Now, one of the hallmarks of the Uncharted series is all its hand-over-hand type climbing. In Uncharted 2, there are several scenes that could be compared to the MGS2 scene I just mentioned. (The train scene at the beginning, the flagpole scene in the Urban Warfare chapter, etc.) The difference is that Uncharted doesn’t make you watch a cutscene while things are falling apart. You are in control the entire time. As metal poles bend and shift under your weight, you get to remain immersed in that moment, with your heart pounding as you try to guide Nathan Drake to safety. Ultimately, these scenes are much more memorable in Uncharted 2 than that post-Harrier fight destruction scene in MGS2, since you are a participant rather than a mere spectator.

To me, this is evidence that video game storytelling is evolving in exciting ways. A movie (or a cutscene) could never deliver the hanging-precariously-from-a-train-car scene with as much intensity as Uncharted 2 did. When you are in control, the danger is real and present; you’re right there in the moment. If you screw up, your character could fall to a horrible death. In a cutscene, you aren’t directly involved; you are a passive observer.

The whole point of this comparison is that MGS2 took a movie-like approach to presenting a scenario, and Uncharted 2 presented some very similar scenes completely in gameplay. Sure, Uncharted 2 is full of cutscenes, but I think it has several moments that stand as evidence of a new direction for video game storytelling: stories that can be told without temporarily sacrificing the interactivity that make them games in the first place.

In fact, several high-profile industry people have come forward and expressed their desire to see this sort of shift. Ken Levine recently told Digital Spy, “People tend to overdo it with their story and not strip it down to the bare minimum. There is a rule that you start the scene as late as possible.” This goes back to my discussion on Iceburg Theory from last week. Levine continued, saying, “A lot of games have that problem in that they don’t understand that—there are long cutscenes and a lot of talking. I try to respect the gamers’ time as much as possible.” He feels that a game developer who constantly delivers lengthy cutscenes doesn’t respect gamers’ time.

And Levine isn’t the only one to feel this way. Guillermo del Toro, director of such films as Hellboy and Pan’s Labyrinth , has expressed his own opinion on cutscenes. He said in an interview—with Ken Levine, of all people—”You know what kind of gamer I am? When we come to a cinematic, I jump it. I go ‘I’m not watching a movie, f*** you.’ I want a game. You can selectively take control away from the gamer for a few seconds, but don’t render him inactive.” Now, this opinion comes from a person who makes movies for a living and is currently working on a horror video game. He understands that video games need to tell stories in different ways than movies.

My prediction: Video game storytelling is finally breaking free from all the limitations of films, novels, and comic books, doing things that would be incredibly difficult—or, in some cases, impossible—in other types of media.

In the next generation, we’ll see this idea expanded upon even further, with stories larger and much more interactive than anything found in a movie or even a long-running television series. If you love storytelling, it’s simply a fantastic time to be a gamer.

By Josh Wirtanen

CCC Editor/Contributing Writer

*The views expressed within this article are solely the opinion of the author and do not express the views held by Cheat Code Central.*