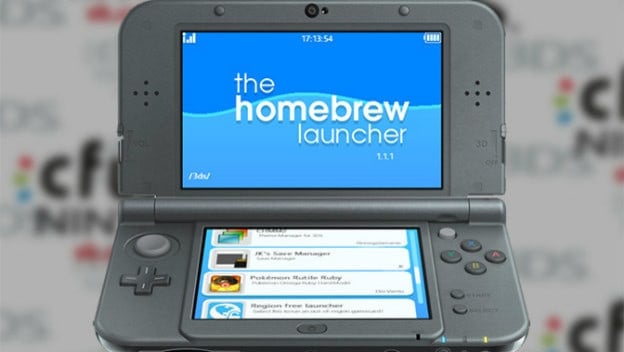

Fueled by the novelty of tinkering and the marvels of hacking, I installed custom firmware on my New Nintendo 3DS. Once a platform sort of outlives its life cycle and becomes more or less irrelevant to my work, I like to see what they can do. The 3DS homebrew scene has been a blast, beating out the PSP hacking scene in terms of cool stuff you can do. From elaborate, user-created themes to running certain DS games in widescreen, diving into 3DS hacks has been a great. Naturally, this venture included messing around with different emulators. As I installed all the old favorites just to see how they ran on this unfamiliar hardware, I found myself thinking on one of my favorite topics: piracy.

Most conversations around piracy are pretty old hat. Usually, those discussions are framed around what damage piracy does or doesn’t cause to creators or (more likely) publishers. Anti-piracy folks are usually gung-ho about supporting the “developers” and the publishers who are actually taking the sale revenue in talk about “lost” sales. This equates piracy to stealing, but as has been pointed out in recent years, large media companies went out of their way to bury research that disproved that a long time ago. Most consumers would rather pay for ease and convenience, hence all the streaming services popping up everywhere.

But despite those conversations, nobody really looks at piracy outside of economics. Instead of thinking about piracy in terms of theft, profits, or supporting creators (the latter of which is important in indie spaces), what about culture? In many cases, the folks out there on the internet doing work to crack games, hardware, and anti-piracy software are doing important conservation work. Even if they’re more interested in finding ways to customize their gadgets, test their skills, or avoid paying for games, hackers and emulation software developers are gaming’s most effective archivists.

Publishers themselves hardly do the proper work to preserve their own content. It’s easy to talk about supporting developers when it comes to selling products, but when it comes to keeping names and art alive through time and obsolescence, things get quiet. Source code is lost all the time. When games do get re-released, they’re often either simple ROM dumps wrapped in custom emulators or things like “remasters” which are cool, but modified. Meanwhile, the originals are either lost to time or preserved via piracy.

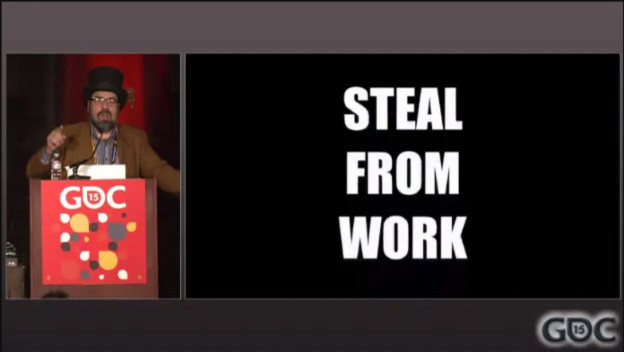

Jason Scott, head of the Internet Archive, famously encouraged GDC attendees in 2015 to “steal from work.” He wasn’t talking about taking things like staplers or company-branded writing utensils. He was referring to code, software, hardware, and anything else that could be preserved for the sake of keeping history alive. But not everybody is going to follow that advice. Hard copies will be destroyed, code deleted, and work erased. At the very least, that kid sitting at home ripping data from Nintendo Switch cartridges is doing important work nobody at Nintendo is doing, because there’s no money in public-facing archival.

Thanks to the gaming community’s continued interest in hacking devices and reverse-engineering consoles, I can continue to access and play games I never knew existed until well after they left store shelves. Games that are delisted from digital services are still alive out there, as long as you can follow some wiki instructions or have a strong enough PC. Even some online games that have long since shut down have dedicated communities running their own, private servers. This is all labor performed out of passion, important work being done outside the realm of profits and shareholders. Piracy isn’t merely justifiable; it’s a moral good. Emulation is for the culture, folks.