Back when polygonal graphics were new and sprite graphics were boxy, it was easy to sell a game based on graphics alone. If you were the first company to have some huge new graphical achievement, you would be the toast of the town.

This was partially because graphical advancements were so easy to notice. The blocks of the Atari were noticeably lower grade than the simple sprites of the Nintendo, which were noticeably worse than the 16 bit sprites and mode 7 scaling of the SNES, which were entirely different from the simple polygonal models of the PlayStation, which were primitive when compared to the fully polygonal environments of of the PlayStation 2 and Xbox.

But then the advancements stopped being so profound. The PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360? Still polygonal models in polygonal environments. The PlayStation 4 and Xbox One? Still polygonal models in polygonal environments. Sure, each successive console looks better than the last, but the graphical style is still the same. The way we looked at graphics didn’t change radically as it did in the 80s and 90s, and so graphical achievements are just a little bit less impressive.

in the days of the NES and SNES, it was conventional wisdom that every game that came out needed to be as graphically impressive as possible. This viewpoint persisted in game development clear through the PS2 era of gaming. But then retro games came along, and things started to change. These games–most of the time made in the indie-sphere, but sometimes dabbled in by AAA companies like Capcom with Mega Man 9 and 10–purposefully used retro style graphics that barely taxed the graphical capabilities of modern day consoles.

There are many reasons to make a retro game. Sometimes, it’s because a developer’s budget is limited. Sometimes, it’s an aesthetic choice meant to invoke a feeling of nostalgia. Either way, when you make a retro game you are actually giving yourself something that tends to make games come out more creative and innovative: boundaries.

You see, back in the days of sprites we couldn’t have high quality photo realistic in-game cut-scenes to tell stories, nor would we have complex in-game tutorials that explained every facet of the game to us. We had to do more with less, and that’s why some of the most well received games of the past are so simple.

Super Metroid never had tutorials beyond small text boxes telling you the basic controls. How you used your new abilities was totally up to the player. The basics of combos in Street Fighter II were never explained, and players had to figure it out for themselves. Real emotion was expressed in our RPGs without voice acting or cutscenes. Heck, the final Giygas battle of Earthbound was terrifying! Emotion could be expressed in just a few frames of animation or a scrolling background.

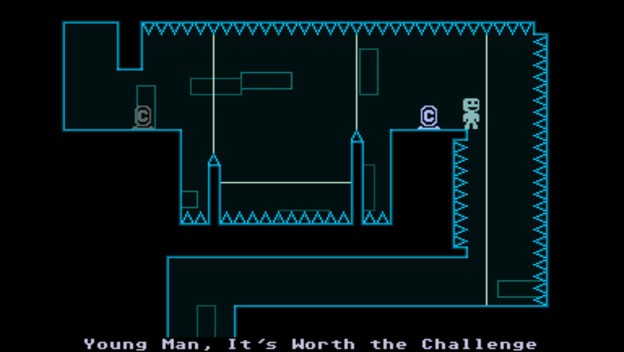

This is basically what retro games are doing today. Nidhogg, for example, is incredibly simple and can be learned without any instruction. It gets across the hype feeling of a fighting game tournament without long combos or complicated zoning strategies. VVVVVV teaches people how to use its gravity flipping mechanics without a single text box. Games like Thomas Was Alone express incredible emotion through nothing more than colored rectangles.

That’s why we need more retro games. We need to learn that graphics aren’t a substitute for gameplay. Riley, the Call of Duty dog, may have been the most photorealistic dog yet, but it didn’t make the game more fun to play. Simply put, if you can make a game fun using simple primitive graphics, then you can probably do the same with a huge graphics engine. Unfortunately, few companies still can capture the wonder of the old sprite and low def polygon days.