Before coming West, Xenoblade Chronicles X altered the way that some of its outfits looked on the 13-year-old Lin Lee Koo. Fire Emblem Fates is altering a scene that could be interpreted as promoting gay conversion therapy (although it was not intended to do so). Now it’s been confirmed that the scantily-clad, headdress-wearing “Tomahawk” job in Square Enix’s Bravely Second will be replaced by a cowboy-themed “Hawkeye” job in the West. If I had a penny for every time somebody in a comments section threatened to boycott one of these titles over “censorship,” well, I’d actually be able to afford to buy them myself with my sadly deflated Canadian currency.

For those who are confused over why the Tomahawk job was altered, it’s likely to show respect for Native American/First Nations people in their home countries. Many native people object to their traditional garb being used out of cultural context and being unrealistically sexualized, both of which can be said of the original Tomahawk outfit. Of course, the Hawkeye replacement job comes with its own set of stereotypes (here’s hoping its Southern accent isn’t something out of Hee Haw ), but however you feel about it, it’s not censorship. Neither are the other recent examples of Japanese games being altered by their creators before being exported from Japan, and neither is the decision not to release certain games in the West at all. We’ve been throwing the word “censorship” around way too freely in the gaming community, and we need to stop.

Censorship happens when a government legally restricts what kinds of things its citizens are allowed to see, read, or play. It happens when lawmakers refuse to allow a movie to be shown in a country because they find its content objectionable. It happens when a school board bans a book from the classrooms and libraries of its district. And yes, it happens when a government refuses to allow a particular game to be sold in its country. Censorship does not happen when a company makes a completely voluntary decision to make a change to its own content.

When we use the word censorship for completely voluntary decisions made by game companies, it lessens the impact of the actual censorship found in our industry. Yes, some countries have laws restricting the kind of content that can be shown in video games. Germany is notorious for restricting depictions of violence in video games, which has led to publishers cutting content or changing the color of blood from red to green so that their games are allowed to be sold normally in the country (Nazi imagery is also banned in Germany, for obvious reasons). China is even stricter when it comes to video game censorship; all games imported into China must be vetted by a government committee and can be banned for reasons such as “disturbing social order” or “damaging the nation’s glory.”

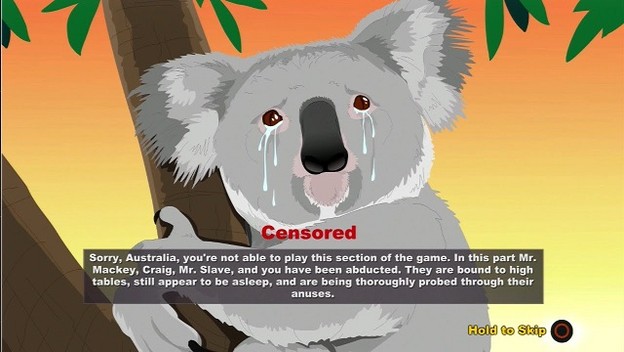

Here in the English-speaking world, Australia has the most vigorous government censors when it comes to video games. It’s illegal to sell games in Australia if they haven’t been classified by the country’s ratings board, and said board hasn’t hesitated to effectively ban games by refusing to classify them for various reasons. Hotline Miami 2 felt the board’s wrath last year due to depictions of sexual violence, and South Park: The Stick of Truth had to censor specific scenes in order to be classified (which it did in gloriously sarcastic South Park fashion). Australia’s game censorship is extremely controversial, but legal shenanigans on the part of the pro-censorship side have, to date, kept it in place.

I hope you can see the difference between these scenarios. In the censorship cases, laws and governments determine what changes need to be made in order for games to be made available in a particular country. In the case of the currently controversial Japanese game edits, companies are choosing to alter their content for Western consumption based on cultural differences and hot button issues. No government institution is stepping in and threatening to ban or restrict the sale of these games if the changes aren’t made. You’re free to agree or disagree with the reasoning behind these changes, but they aren’t censorship. They’re marketing decisions. The companies in question have decided that these changes will increase their sales by avoiding controversy. They know that a portion of their consumer base hates these types of changes, they’ve apparently decided that a few lost sales from those consumers are acceptable compared to the gains they think they’ll receive (be they directly through increased sales or indirectly via reputation) by adjusting to cultural differences.

You know what we call that? It’s not censorship. It’s capitalism.